Speak of the Devil, and the Devil Doth Show Up In a Giant Spaceship

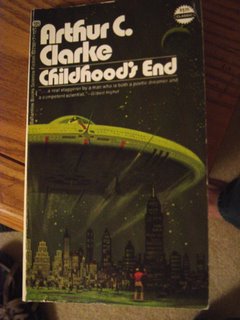

Latest off the skillet is Childhood's End, by the eminent Arthur C. Clarke (entertaining picture alert). As part of the spoils of the Friends of the Library Booksale, it began with the twin desirable qualities of being virtually free and having a campy 1970s SciFi cover, pictured below:

Additionally, this was a book that I had been wanting to read for some time, after stumbling upon it while reading Wikipedia, probably rooted from this article about "The End of History." That's a tiny little spoiler right there, and before we go any further, let me just warn you that many more will follow forthwith.

This book is pretty amazing. There's two kinds of SciFi in the world: one is Star Wars style, where a bunch of cowboys and Indians shoot lasers at each other In Space, and the other kind is this. It's about imagination, the future, and, yes, the human condition. This book makes you think, which, while cliche, is absolutely true - you will be thinking throughout the duration of this book.

The beginning is about this question: if you could have world peace, end world poverty, and world hunger, and make everyone happy, but it was all imposed at the point of a gun, would you take it? It's about the end of all sovereignty, the end of democracy, and the end of all say over your own government. But you and everyone else gets to be completely happy.

When the UN rules the world and the new "World Constitution" goes into effect, you're sympathizing with the resistance groups, but then you start to think - maybe everyone really is better off this way. The only negative aspect is one of principle; humanity isn't free du jure, but it is free de facto - and with all the problems of the world solved anyways, what is the point of principle? Clarke keeps you teetering right on the knife edge here; it's really difficult to decide who to root for. In the end, it doesn't really matter - the outcome is inevitable, when faced with The Overlords.

The second part is about a Utopia, and all the philosophical questions that are standard for the idea. Humanity is faced with a world where no one has to work unless they want to, where the average American watches (gasp!) three or more hours of TV a day (circa 1950, this was a big deal), and no one has really done much of anything in the realm of science, art, or just about anything else for quite some time. There just doesn't seem to be any point anymore. Again, you sit right on the edge of this section - you feel pity and envy for the people of this time. Life is wonderful, but they have nothing to live for.

I won't spoil the end, because it is fantastic and partially dependent on suspense, but it deals with the end of childhood (as you might guess from the title), for humanity. Much is gained and much is left behind and lost forever - again you are left wondering if it was all worth it, if it wouldn't have been better to stay the way it was... but, as with the rest of the book, the change is inevitable. You still can't help but feel a little sad, though.

If you're not interested in the thinking stuff or the mushy stuff, the core story is still probably enough to pull you through the whole book. Clarke keeps you going, gradually revealing secrets about The Overlords, their motives, their plans, and their nature. The characters are interesting enough and less stuffy than typical 50's SciFi people. Since humanity is still in "modern" times and all of the technology is alien and intentionally kept behind a veil, it doesn't suffer from the quaintness that a lot of old SciFi does.

Yes, that's right - this book has everything. It's a recognized classic of SciFi, and with good reason. The proselytizing blurb on the back of the book is spot on when it says:

In the literature of our time, CHILDHOOD'S END will surely stand as a landmark. And it is not any accident that it is science fiction. For science fiction, more than any other literary form, truly expresses the ambiance of the 20th century. The authors of [a bunch of scifi books], and many more brilliantly perceptive novel, write from an awareness and sensitivity that illuminate the human condition.

Okay, maybe that guy went a little overboard there, but seriously, read this book.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home